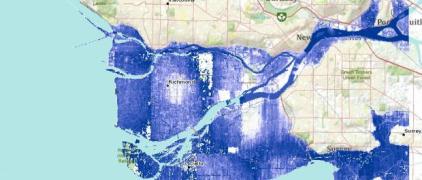

In 2012, a BC-commissioned report, Cost of Adaptation – Sea Dikes & Alternative Strategies, estimated costs of $9.5 billion for 250 km in flood protection in the Lower Mainland accounting for a one-metre rise in sea level by 2100. This report signifies the challenge and importance of protecting significant assets and adapting to projected climate impacts (e.g. managed retreat) at the local and regional scale.

This cost information exists within a larger global discussion about the costs of action and inaction on climate change. In 2006, the Stern Review argued that if we don’t act now, spending 1% of global GDP each year to curb emissions and avoid the worst impacts of climate change, the overall costs would be equivalent to losing at least 5% of global GDP each year, up to 20% per year. The message was clear, the longer we wait to undertake emissions reductions, the greater the costs will be over time to do so. In 2007, evidence from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) made it clear that climate is changing faster than previously thought; implicit in this recognition was a clear statement that adaptation to projected climate impacts, such as sea level rise, is inevitable. With new scientific information, in 2008, Stern revised his estimates, stating that due to acceleration of climate change, the costs of inaction would likely double original estimates. This is particularly true as governments continue to authorize the development of assets in vulnerable areas increasing the risks and approving emissions-enhancing activities in their jurisdictions, increasing the severity of impacts.

In Canada, the 2012 release of the National Round Table on Environment and Economy’s report Paying the price: the economic impacts of climate change for Canada, argued that the economic impact of climate change on Canada could be up to $5 billion per year by 2020, rising to between $21 and $43 billion per year by 2050. Flooding damages along the coastlines from sea level rise, storm surge and increased weather events was estimated to be on average between $1 billion and $8 billion per year to 2020. Additional impacts and damages are projected for timber supply, particularly in BC, and health impacts from poor air quality in four of Canada’s main cities, including Vancouver.

What is interesting about these cost estimates is what scale of action we choose to act and where we choose to be on the cost range over time. There is a choice about whether to incur costs of 5% or 20% global GDP each year. The range is dependent on our global emissions trajectories; we currently remain on the upper end of the range. The question then becomes, what can be done to significantly curb emissions that limit the speed and severity of projected climate impacts over time, reducing costs over time, and at what point in time is it most cost-effective for these actions to be undertaken. Both the costs of action and the costs of inaction increase over time. The message gives rise to the ultimate co-benefit between adaptation and mitigation: taking swift and strategic actions earlier rather than later to reduce emissions will cost less and also reduce the costs of the projected impacts of climate change over time.