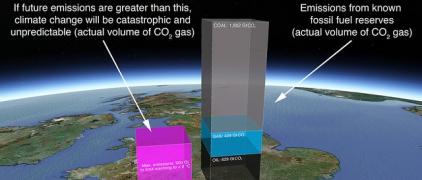

Global future emissions and fossil fuel reserves. Source: Carbon Visuals

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has forecasted a 30% expansion of the total global energy needs between now and 2040. While electric cars are helping to slow this down, the petrochemical industry together with commercial transportation including trucks, aviation and shipping are keeping oil demand in a rising trend (IEA - World Energy Outlook 2017).

Nonetheless, there is a growing belief that in the near future, fossil fuels might become stranded assets. In other words, they could be non-viable and considered as liabilities as a result of devaluations.

In this regard, investors and large companies are exploring a different angle around the debate to divest from fossil fuels. As oil price falls, a number of unconventional oil sectors, such as oil sands, shale oil and Arctic drilling, have quickly become less profitable, shifting the divestment debate from policy to economics.

As a 2015 report by the HSBC global research on climate change already indicated: to consider fossil fuels as stranded assets is not an overstatement. They identified three main drivers:

- The first driver was related to the increment of the cost of carbon, driven by regulations in an increasing number of countries, taxing carbon and creating emissions trading schemes.

- The second driver was the decrease in energy commodities, which makes the development of specific assets and reserve classes progressively unprofitable.

- The third driver was the energy innovation (including renewables, battery storage and enhanced oil recovery), where efficiency gains affect negatively the demand and technology drivers increase supply and reduce demand.

Even considering a decrease in production costs, all of the above was considered by the 2015 report to result in further stranding of high carbon and high cost fossil fuels.

Since then, HSBC investors have decided on how to best manage the growing risks of asset stranding. They did so while considering the reputational and economic risks involved in maintaining investment in fossil fuels, as well as the risks associated with overly concentrating their portfolio of investments with 100% divestment.

In the end, the 7th largest bank and the largest European bank (with over US$ 2 trillion in assets worldwide), announced their plans to no longer finance the worst climate offenders by “closing relationships with those who do not meet minimum standards"! To “help customers transition to a low-carbon economy”, HSBC announced last week that they will divest from new coal-fired power plants, Arctic drilling or new oil sand projects, including pipeline investments in oil-rich Alberta.