Dr. Alison Shaw

Research Manager, Associate, Meeting the Climate Change Challenge (MC3), Royal Roads University

Published February 8th, 2013

Case Summary

Carbon Neutral Kootenays (CNK) began as a response to the Province of BC’s 2008 Climate Action Charter. Due to the Charter 2008, regional and local governments across the Kootenays made independent commitments to reduce energy and carbon dioxide emissions yet there remained considerable uncertainty about how to achieve the carbon neutral mandate. Individual leadership at the regional government scale spurred innovative and strategic thinking about how to practically implement these commitments as a regionally-based collaborative governments network. In 2009, Chief Administrative Officers (CAO) from the Regional District of the Central Kootenay (RDCK), Kootenay Boundary Regional District (KBRD) and the Regional District of East Kootenay (RDEK) together, with the Columbia Basin Trust (CBT) formed a Steering Committee in 2009. This collaboration, CNK, lead to the development of baseline energy and emissions inventories and action plans across a broad geographic scope, spanning 3 regional districts, 29 local governments and 6 First Nations in the southeast corner of the Province. Three notable innovations emerged from this process:

- intergovernmental and cross-scale collaborations,

- inclusion of small, rural municipalities and electoral areas that otherwise not have participated in climate action,

- and the development of a regional offset strategy to harness offset funds for regional emissions-reducing projects.

Intergovernmental and cross-scale collaborations

The leadership and collaboration demonstrated by the Chief Administrative Officers (CAO) from the three regional districts meant that resources were pooled in order to better optimize political, financial and scale benefits of aligning efforts. The knowledge and financial support provided by the Columbia Basin Trust, played a crucial role in establishing and coordinating terms of reference and details for the collaboration. For the regional districts, this was a trustworthy partner with a mandated interest in the advancement of the Kootenays. For CBT, approaching carbon neutrality streamlined their own efforts to encourage and support local governments in this goal.

To initiate the CNK project all four organizations pooled an equal share of funds ($50,000 each) toward the original goal of procuring a contractor to help the project in its efforts to develop baseline inventories, reduce emissions and assist Kootenay local governments achieve carbon neutrality by December 2012. Together, the collaborators jointly issued a request for proposal (RFP), broken into three Phases. A collaborative team of consultants was hired to help to achieve this.

In 2009, a partnering team of consultants from Stantec (previously known as the Sheltair Group) and the Community Energy Association (CEA), performed energy and emissions baseline inventories for the 3 Regional Districts, 29 participating local governments and 6 First Nations. The first phase focused on measurement, education and training.1 In Phases 2 and 3, (2011-2012) consultants continued to assist in action planning, inventory maintenance and implementation efforts among regional and local governments.2 A final legacy goal of Phase 3 was to evaluate opportunities for a regional offset strategy that would keep offset funds within the region (pers. comm. [1][3][9]; CBT 2012).

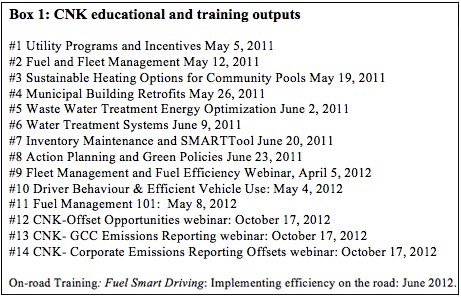

The consultants used a number of educational and outreach strategies to raise awareness among and share ideas to the communities regarding emissions reduction strategies. These strategies included a series of webinars with topics ranging from fleet management to energy-efficient building retrofits to energy and emissions inventory maintenance (see Box 1).

Borrowed from CEA http://www.communityenergy.bc.ca/take-action/webinars-2011

In addition, since the initial joint procurement of CNK consultants in 2009, other collaborative procurement strategies have emerged. These include has fostered economies of scale, reducing costs for participating local governments through the joint procurement of expertise (and materials). For instance, building energy assessments, creating opportunities for reducing energy, optimizing wastewater energy and assessing alternative energy opportunity were performed for more local governments interested in participating.

Inclusion of small, rural municipalities and electoral areas

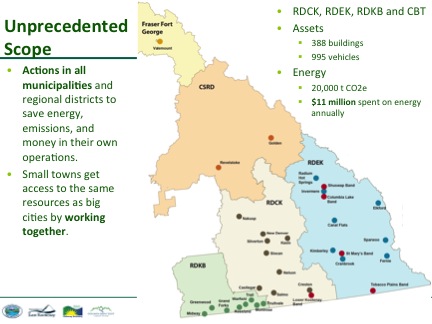

A critical innovation and success of the CNK has been that 100% of the 35 participating local governments and First Nations have taken some action to reduce energy, emissions and save money (pers. comm. [1]).3 This has occurred despite size, capacity and regional disparities, which would not have occurred without the regional network. An emphasis on the cost-effectiveness and cost-savings of actions to reduce energy consumption, by reducing fuel and electricity costs and ultimately, offsets, has been a critical driver of action for local governments in the region. This has lead to an unprecedented level of coordination and geographic scope for reducing energy and emissions in the province (and elsewhere) (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1 (Littlejohn, 2012). Carbon Neutral Kootenays. RDCK Project Update, presentation February 16, 2012.

Although, interviewees have noted that significant greenhouse gas emissions reductions have not occurred over the short period of time of the project (pers. comm. [3][5][7][9]). This is largely due to political cycles and financial and administrative capacity that usually require up to three years for planning and implementation.

The development of a regional offset strategy

Apart from this unprecedented level of collaboration, another key climate innovation in the CNK is the development of a regional offset strategy. Currently, the Darkwoods Conservation Project is being finalized with the Nature Conservancy of Canada. 2012 offsets for CNK participants will be purchased from the Nature Conservancy to manage conservation efforts in the 136,000 acre Darkwoods property, and to build an endowment in the Kootenays.4 Once approved5, the Darkwoods regional offset project will create a precedent for communities working together to reclaim offset money for emissions reductions projects within their region. The Darkwoods Conservation project currently is the largest private conservation initiative in Canada and is set to become the largest forest carbon offset project in North America.6

The CNK regional network enabled the co-ordinating conditions for this precedent-setting project. Through the CNK, the region shifted from disparate small, rural communities to a more visible and elevated role as a unified region in the province. The collaborative success of CNK in climate action has created critical mass, bolstered its credibility, ultimately influencing approval, by the provincial government, of regional offset strategies (pers. comm. [3] 2012). In addition, the groundwork has been laid through the CNK for a collaborative governance model that would pool Climate Action Revenue Incentive Program (CARIP) offset grants into what is likely to be a Kootenay Carbon Trust (likely to be overseen by the CBT). Applications would then be accepted for emissions reducing projects delivered by governments and/or community members. The specific model for the regional offset strategy is still being configured; however, the general concept is to generate regional commitment toward reducing energy consumption and emissions while also building a green economy.

Sustainable Development Characteristics

The CNK demonstrates how emphasizing energy and emissions baseline inventories and generating conditions for learning and exchange through the various activities outlined in Table 1 can facilitate cost-effective action on climate change. Learning about local assets and energy costs occurred through the energy and emissions inventory process. This awareness generated alongside the collaborative support by local governments to take action to reduce emissions at this geographic scale, is contributing to the province’s goals of carbon neutrality. Of interest is whether these climate actions are also simultaneously contributing to a more sustainable development trajectory in the region. While this is difficult to judge, and would certainly be different on a community-by-community basis, a number of interviewees noted that the overall awareness generated by the energy and emissions inventory and accounting process has already contributed to changes in the calculus most local governments use to implement longer-term energy and infrastructure decisions (pers. comm. [1], [5], [8]).

Sustainable development characteristics for this case have been categorized as they pertain to environment, social equity and economy, and are listed below.

Environmental

- 35 municipalities and 6 First Nations completed CEEP baseline inventories identifying and reporting key energy and emissions sources in buildings, fleets and overall operations. This included municipalities from 160 people to larger communities.

- Simplified reporting structures enable even the smallest communities with the least capacity to deal with the new carbon neutral reporting requirements.

- Developed reporting tools and templates ensure capacity for energy and emissions reporting into future and to share with other regions and communities (pers. comm. [8] 2012).

- Education and awareness-building about relationships between climate change, emissions and municipal assets and decisions primarily among municipal staff and officials.

- The Darkwoods Conservation project operates as the largest private conservation initiative in Canada and the largest forest carbon offset project in North America at this time.

Equity

- Developing a strong, “mature” collaborative partnership that pooled funds ensured that all participating communities in the Kootenays were accounted for regardless of their size or location (i.e., remoteness).

- Capacity-building at a broad regional scale was central to the development and success of the CNK. Baseline knowledge and capacity in the form of energy and emissions inventories, educational webinars and workshops and training, was available to all participating communities, even small and rural communities that otherwise would not be included. In addition, significant improvements were made to all communities in better understanding their asset base and improving the ability to manage it.

- Spurring solidarity: that others are responsible for doing this too “provides the feeling that we’re all in this together” (pers. comm. [5]).

Economic

- Cost efficiencies were created through joint procurement initiatives at the regional scale; sharing expenses for expert training for and analysis of building audits and assessments, alternative energy opportunity assessments and wastewater treatment plant energy assessments minimized costs that would otherwise be born by local governments independently.

- 100% of participating communities have taken actions to reduce energy consumption; many were motivated by the ability to save money by conserving energy. Many local governments now have holistic accounting of assets that otherwise would not have and are able to identify areas to increase efficiencies, conserve energy and save money (pers. comm. [1], [2], [5]).

- Ultimately, the regional offset strategy pools offset funds for regional retrofits/upgrades/green economic development.

Critical Success Factors

Provincial leadership through a level playing field legislative framework, the Climate Action Charter, was the driver for encouraging communities to take responsibility for their energy and emissions and to meet carbon neutral targets by 2012. Individual leadership, at the regional government scale, was a driver for the collaborative model used to address the requirement to meet the Charter’s carbon neutral targets. The Central Kootenay’s Chief Administrative Officer (CAO) initiated dialogue with the other two CAOs in Kootenay Boundary and East Kootenay and with a representative from the Columbia Basin Trust (CBT) collaborated to better understand the opportunities for collectively addressing the Charter from a regional perspective.

CBT is an intermediary organization created to support locally-led intiatives that improve ecosystems and well-being in the Kootenays. CBT’s funding allotment from the province is mandated to be locally-driven and is designed to be distributed to projects and activities contributing to the betterment of the Kootenay region. The organization arose from a response to the significant hydroelectric projects that have been a sizable economic boon for the province (e.g. selling electricity to the US) and the need for communities in the region to derive some benefit. In this case, the CBT played a fundamental facilitative and partnership role in the creation of CNK. Familiar with the political and geographical terrain, CBT, using the experience and trust they have built in the region, were able to facilitate dialogue among the regional governments about a coordinated approach, help to set up the CNK Steering Committee and develop terms of reference for the collaboration. With a mandate to support the development of the Kootenay region, they also provided one-quarter of the funding support. In addition, the regional approach was appealing to CBT. Working directly with three regional districts to help address climate action, was far more streamlined than working with 35 local governments and First Nations.

CNK’s inclusive approach (i.e., including communities with a population as small as 160 people) helped build the internal capacity in each local government (e.g. understanding building, fleet and infrastructure assets) while also contributing to a collaborative regional model. The baseline inventories, awareness building and training administered by the consultants contributed to building this capacity. This capacity-building has been developed over iterations with changing political cycles in local governments. In a number of cases, decision-making processes were changed to account for the cost effectiveness of energy savings strategies over the long-term, based on having established a baseline inventory alone (pers. comm. [1], [7] 2012).

The CNK’s collaboration, and development of a regional Kootenay identity, is likely a significant contributor to the momentum attached to the innovative regional offset initiative. Currently, Kootenay governments spend about $11 million per year on energy and generate about 20,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide. The projected combined Kootenay carbon footprint requires that approximately 21,000 tonnes of CO2 eq per year, or $525,000 worth of offsets will be required among participating municipalities to meet the carbon neutral objectives.7 The Darkwoods Conservation Project is the only project at this point with the ability to meet strict offset criteria. Negotiations have not been finalized; however, $25 per tonne has been suggested as an upper limit offset price. Local governments offset calculations must be completed before the end of February 2013 and be invested before the deadline of March 8, 2013. Keeping these funds within a region of this scale is perceived to be a boon for visible emissions reductions projects and for circulating funds within local economies.

Community Contact Information

Jim Gustafson

Chief Administrative Officer

Regional District Central Kootenay

Box 590, 202 Lakeside Drive

Nelson, B.C. V1L 5R4

Toll-Free: 1-800-268-RDCK (7325)

Phone: (250) 352-6665

Fax: (250) 352-9300

jgustafson@rdck.bc.ca

Kindy Gosal

Director, Water and Environment

Columbia Basin Trust

Tel: (250) 344-7015

kgosal@cbt.org

Dale Littlejohn

Executive Director

Community Energy Association

Suite 308 402 West Pender Street

Vancouver, BC, V6B 1T6

Tel: (604) 628-7076

Fax:(888) 864-3358

dlittlejohn@communityenergy.bc.ca

What worked?

- Collaboration among regional governments and intermediary organization.

- Streamlining the regional-scale model for CBT. It is easier to work with three regional districts than 35 municipalities and First Nations.

- Awareness creation and capacity building for communities and local government staff.

- Establishing corporate energy and emissions baselines in 35 local governments and First Nations.

- Better understanding of corporate assets and operational costs in local governments – translated into better understanding of associated energy costs and emissions.

- The province’s distinction between corporate and community energy planning was viewed both as a constraint and an opportunity. It was perceived as an opportunity because it allows governments to lead by example, having concise and discrete requirements (as demonstrated in the SmartTool). The calculus for corporate energy and emissions is relatively simple and can successfully be monitored and reported.

- Collaboration leading to economies of scale in joint contracting and joint procurement. The initial Carbon Neutral Kootenays contract jointly procured the services of the Stantec/Community Energy Association team. This collaboration led to additional procurement strategies with consultants.

- Initial approval and infrastructure for regional offset strategy through the Darkwoods Conservation Project.

What didn’t work?

- Slow moving political systems and “the natural timescale associated with local governments” (pers. comm. [1] 2012). Consistent political leadership in a system with (relatively) frequesnt election cycles is difficult to maintain, especially when dealing with the cycles involved in all 35 participating municipalities and First Nations in the region. Due to the political cycles in these varied communities, consistent awareness and capacity building were required in order to maintain interest, enthusiasm and capacity.

- The lack of capacity in local governments across the region. Many interviewees cited the need for dedicated staff both in regional and local governments. In order to maintain climate change and sustainability profile, a staff member needs to be writing reports and keeping the issue as priority on politician’s desks (particularly with waning interest in the provincial government). For staff, there is a lack of incentive to do this without a clear work plan mandate. Other competing priorities often take precedent on their desk and in budget cycles.

- Investment decisions, for things such as alternative energy technology, that extend beyond 3-5 years are difficult to justify without demonstrated rates of return on investment (there is sensitivity about incurring liabilities on a future board). One interviewee noted the irony that local governments can borrow loans that extend up to 20 years but how it is very difficult to make and justify commitments for future boards in the service sustainability (pers. comm. [3] 2012). It should be noted, that this perception of fiduciary risk over the long-term is often associated with an ideological framing of sustainability rather than a practical, cost effective framing of sustainability over the long-term.

- The province’s distinction between corporate and community energy planning was viewed both as a constraint and an opportunity. It may be a constraint because of missed opportunities for synergies and linkages to community-wide energy and emissions planning (pers. comm. [6] [9] 2012).

- Maintaining political and public interest. When provincial enthusiasm wanes, it becomes more difficult to justify expenditures of money and time. However one interviewee notes that public reporting, with stringent performance measures, may spur continued interest (pers. comm. [8] 2012).

Financial Costs and Funding Sources

Phase 1-3 (3.5-4yrs): Consulting contracts (>$440,000).8 The expected costs of designing and supporting the roll-out of a regional offset strategy are approximately $120,000 annually.9

The CNK resulted from a unique collaborative funding model among three regional governments and a quasi-institutional intermediary, CBT.

Research Analysis

An interesting thing to note in this case study is that it is an innovation that emerged by a key leader, and those willing senior regional government actors, who argued that fulfilling the Climate Action Charter commitments was a collective challenge requiring an unprecedented level of collaboration. A combination of events that most Kootenay communities signed onto the Climate Action Charter and that a Chief Administrative Officer (CAO) demonstrated leadership in working together to figure out how others were approaching the mandate of being carbon neutral by 2012, spurred the collaborative potential that has since evolved in the CNK. Three “mature” CAOs, in collaboration with a unique intermediary organization, CBT, contributed to the trust needed to jointly procure and fund the CNK project. The sentiment that ‘working together will get us farther’ defines this particular case and has contributed to climate action at a significant geographic scale. With a population of approximately one quarter of a million people, CNK is significantly less than the provincial urban centres of the Lower Mainland or Capital Regional District; however, the geographic expansiveness and diversity of the project’s respective region positions CNK as an innovative and important hub for the province.

Both CNK phases required considerable education and training in order to guide governments on how to measure and monitor energy and emissions data. Maintaining a level of education, awareness and function (for instance, among staff trained to use the Province’s SmartTool) became an ongoing process amidst diverse political affinities and agendas and wide-ranging staff capacities. As a number of interviewees noted this was not as simple as it sounds. Many municipalities were not even aware of what their overall asset portfolio looked like (pers. comm. [1][5], 2012) including number of buildings as well as square footage of buildings, energy consumption figures and types of energy used for heating and operations. Educational webinars ranging from climate change awareness to fuel and fleet management to sustainable heating options for community pools were undertaken to build common awareness about diverse energy efficiency and emissions reducing options available to participating governments.

While the framing of the CNK task was based on climate change and carbon neutrality, the awareness generated from the inventories around assets and energy consumption helped local governments frame energy conserving activities as cost savings activities. In the process of energy and emissions inventory and monitoring efforts, staff and municipal officials became far more aware of their assets, energy use and areas for cost savings in these domains. Local government efforts to reduce costs on electricity and fuels, and also on annual offset payments, contributed to a fundamental shift in their perspectives. A number of interviewees made reference to this as a significant shift in the consciousness of local government decision making, which, in itself, facilitated greater consideration of corporate energy consumption and provided staff and decision-makers with strategies for reducing energy related costs (pers. comm. [1] [3] [5] [8]).

The regional offset strategy became a call to the province to identify and acknowledge the capacity that had been developed in the region since 2009 and to approve an alternative offset purchasing infrastructure (distinct from the provincial Pacific Carbon Trust). The goal of the regional offset strategy began as a response by local governments to prevent their communities from sending cheques to the province (pers. comm. [3]). Strong cultural metaphors of local pride and claims to self-sufficiency in the Kootenays, contributed to the idea that offset money should be not leaving the region but should contribute to emissions-reducing activities and economic development opportunities within the region.10 In this way, the regional offset strategy was an innovation that integrated emissions-reducing activities into existing cultural norms. The idea was to fund and make visible regional emissions-reducing projects and to build on an emerging sense of regional and self-sufficient pride.

Detailed Background Case Description

The climate file is driving a lot more collaborative action amongst local governments (pers. comm [1]). The scale of Carbon Neutral Kootenays and collaboration at the regional government level enlarged the scope of involvement to include small and rural communities, bringing in communities that otherwise would likely not be accounted for. Together, the Columbia Basin Trust (CBT) and the Chief Administrative Officers (CAO) from the three Kootenay Regional Districts - Central, Boundary and East Kootenay - developed a Steering Committee and set out to “develop a coordinated regional approach and plan to assist local governments to achieve carbon neutrality and emissions reductions targets” (CBT 2009). The key driver of this innovation was to strategically respond to the goals of the Climate Action Charter and to create coherence among the diverse regional, local and First Nation governments in the Kootenay Region.

The CBT is an intermediary body with an agenda to help communities and, in this case regional districts, aids locally-led initiatives that increase the well-being of communities in the Columbia region. CBT formed in response to “support social, economic and environmental well-being and to achieve greater self-sufficiency for present and future generations” in the Columbia Basin. CBT emerged from being a local response committee active in securing community interests in the face of the Columbia River Treaty. In 1995, CBT became the organization responsible for distributing a portion of provincial revenues, resulting from the hydroelectricity generated from the Basin, back to communities to secure the social, ecological and economic well-being of the region. In 2009, by request of the regional districts, CBT helped to coordinate the terms of reference and conditions for the proposed carbon neutral Kootenays collaboration.

Strong leadership from the CAO of the Regional District of Central Kootenay (RDCK), with the support of an Executive representative at CBT, encouraged the aligning of efforts with the other two “senior and mature” CAO’s in the surrounding Regional Districts – Boundary and East Kootenay. These four parties developed the CNK request for proposal (RFP), resulting in consulting services by a partnership between Stantec (previously the Sheltair Group) and Community Energy Association. The RFP was broken into three phases. The first phase was to develop CEEPs for all participating governments and to develop educational modules/workshops to raise awareness among community officials and staff as well as the broader Kootenay public. The second phase was to support regional and local government action plans, inventories and implementation and the third phase was to develop a regional offset strategy.

Many governments included in this collaboration had signed the Climate Action Charter in 2008 and all three regional governments had, yet due to the small and varied sizes of the electoral areas and municipalities, there was uncertainty about how to move forward. The Kootenays are represented by varied conditions and cultures between and within regional district boundaries. For instance, there are six communities within RDKB alone with populations under 1000, and for these municipalities (and electoral areas), energy and emissions considerations are difficult due to short supply of human and financial capital. A key success of the CNK has been to bring in communities that would otherwise not be concerned or committed to increasing efficiencies and/or reducing emissions into the project’s fold.

Efforts were already underway in the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary (RDKB) for developing policies and strategies for reducing per capita footprints both in land area and in energy use. For instance, the City of Nelson is well-positioned to retain much of the energy that leaves its jurisdiction every year. Due to the unique service of Nelson Hydro, the City has been exploring ways to harness the $30 million spent on energy annually that leaves the town, in order to stimulate the local economy.

Communities such as Nelson and Castlegar took the lead on energy and emissions planning, even prior to the Charter, and the initiatives of these cities were showcased as some best practice examples in the region; examples include retrofitting public buildings, building LEED platinum municipal buildings, promoting innovative transportation options such as bike lanes and car-sharing. While there were a number of initiatives occurring, the Climate Action Charter reinforced the challenge and begged questions of how carbon neutrality was going to be achieved.

Enthusiasm was high both in the Campbell government and with collective commitment among municipalities at the annual Union of British Columbia Municipalities conference. In the RDKB, the CAO knew that holding a referendum for a new government department was questionable and would likely not pass. From his perspective, the only way to move forward was to form some sort of partnership and charge it under general administration. If done alone Castlegar and Nelson would have survived though smaller communities would have been pressured by a lack of resources. Taking the challenge on collectively was considered a way to utilize the different skills and resources of the three regional districts while also addressing disparities among communities. In addition, the idea of a collective response facilitated partnership to meet the challenge in a unified ways. As one interviewee noted, “Council loves partnering. It's a lot easier for Council to A) go along with the flow when there is a flow and B) to go along with the idea that it's 50 cents or 20 cents or 70 cents… [not 100%]. They love that stuff, at least here. Love the idea of being part of a bigger team. To sell it, it's alot easier to do it in partnership” (pers. comm [5]).

Working in isolation, there is little a regional district can do with $50,000 [1], particularly a regional district like the RDCK, which has a number of electorate ridings and 6 communities with populations under one thousand people. Working in conjunction with other regional districts, each possessing different skillsets and different access to resources generated collaborative potential with the ability to leverage capacity among the regional districts and diverse local governments in order to fulfill the 2008 Climate Action Charter commitments. In addition, collaboration increased the region’s capacity and resources (such as social capital) allowing it to become a significant provincial player. As one interviewee noted, a regional district on its own has limited political stature but a geographic region of province may get some attention (pers. comm. [3] 2012).

Baseline Inventories as a Mobilizing Force

The goal of monitoring and recording energy consumption and emissions for baseline inventories, lead to helping local governments identify and understand their asset portfolio and build their own knowledge skills in the process. Often parameters such as what types of fuels were used to heat buildings (e.g. propane) or what vehicles accounted for how much mileage and type of fuel (e.g. diesel) were in many cases unknown. The development of energy and emissions baseline inventories meant that consultants, in many cases, worked closely with participating government staff to make their asset portfolio visible. This has been an additional of the process.

A number of interviewees mentioned that understanding assets and energy consumption has in and of itself changed the nature of what gets accounted for in decisions. Communities now have an energy calculus in their decision-making framework that is accounted for in large-scale decisions such as efficiency design and energy technology in new municipal buildings (pers. comm. [3][5][6]). For instance, in an interview with a CAO from a small Kootenay town, who self-identified as a climate change denier, explained how their new municipal buildings were LEED design and geothermal heated despite a radically opposed Council. This result was due to the cost effective rationale of lower energy consumption and lower cost fuels over time and the “belief” among the public that action was required. Of note, this particular case also demonstrates the power of public support and the importance of developing climate-aware constituents.

The CNK case provides evidence that educating local governments about their asset portfolio and total energy throughputs and costs, in some cases provides the data needed to make the case for the cost-effectiveness of energy efficiency and rates of return on alternative energy technologies over time.

Education and Training Raises Awareness

The active aspects of CNK climate action have consisted of awareness-building about the Climate Action Charter and corporate energy and emissions planning. Consultants have provided 200 business days (measured per person) of educational and workshop sessions for community members, staff, councilors and board members to attend in order to increase literacy and build capacity for climate action (pers. comm. [1]). In a project of this scale, the multitude of turnover of elected officials requires continual education and reinforcement to maintain literacy and support for the CNK. A number of learning strategies were employed to do this primarily through webinars, workshops and training sessions (see Box 2).

|

Box 2: Different awareness building strategies

|

Taken from CBT http://www.cbt.org/Initiatives/Climate_Change/?Carbon_Neutral

A Regional Offset Strategy

Arguably, the most innovative aspect of the CNK project has been the exploration of the potential for a regional offset strategy. The development of a regional offset strategy, beginning with the Darkwoods Conservation project in late 2012, has been viewed as a way to instantiate support among Kootenay governments. The creation of a provincially-approved, regionally administered offset strategy and infrastructure that pools carbon offset money from municipalities and First Nations in the region could keep up to half a million dollars in offset funds within the region.11 The Darkwoods Conservation project is the only offset suitable project, fitting within rigorous criteria, at this point. This type of Kootenay-relevant, emissions-reduction project is viewed as a way of addressing strong resistance to sending offset dollars to the province, keeping offset dollars local, eliciting strong support for regional climate action and overall, accelerating local government commitment to climate action. In addition, the Darkwoods Conservation project currently is the largest private conservation initiative in Canada and is set to become the largest forest carbon offset project in North America.12

Strategic Questions

- What does the CNK project demonstrate about the benefits and trade-offs of regional-scale collaborative action?

- What were the most seminal ways that information was disseminated and shared among local governments of varying size and with varying degrees of interest in the climate file?

- To what extent is a regional offset strategy financially viable within the Kootenay region’s borders? What are the key criteria required to make this work?

Resources and References

CBT 2012. Carbon Neutral Kootenays. Columbia Basin Trust. Retrieved June 2, 2012 from http://www.cbt.org/Initiatives/Climate_Change/?Carbon_Neutral.

CBT 2011. Taking Action on Local Climate Change and Cutting Energy Costs (August 10). Retrieved September 2012 from http://cbt.org/newsroom/?view&vars=1&content=News%20Release&WebDynID=18…

Littlejohn 2012. Carbon Neutral Kootenays. RDCK Project Update, presentation February 16, 2012.

McDonald&Littlejohn 2010. Carbon neutral ACTION guide: A starting point for local governments. Prepared for the Carbon Neutral Kootenays Project Steering Committee.

CEA. Carbon Neutral Kootenays 2 guide to the inventories. Community Energy Association. Retrieved July 4, 2012 from http://www.communityenergy.bc.ca/take-action/cnk2documents.

CEA. Carbon Neutral Kootenays 2 webinars and events. Community Energy Association. Retrieved July 4, 2012 from http://www.communityenergy.bc.ca/take-action/cnk2

UBCM. Community Excellence Awards Application, Union of British Columbia Municipalities. Available as an attached document at Regional District Central Kootenay website retrieved August 8, 2012 from http://www.rdck.bc.ca/publicinfo/climate_change/carbon_neutral_kootenay…

1The consultants (i) performed baseline inventories for participating governments on energy and emissions, (ii) developed Carbon Neutral Action Plans for the three Regional Districts and assisted in implementing them by 2012, and (iii) educated and trained 35 participating governments and First Nations on energy and emissions reporting. return to text

2This involved developing education and policy initiatives to help guide participating governments on efficiency upgrades within buildings, fleets and infrastructure networks. return to text

3Verified in the Climate Action Revenue Incentive Program (CARIP) reporting done for the Ministry of Communities, Sport and Cultural Development. return to text

4Bennett, Andrew 2012. Carbon Neutral Kootenays – Darkwoods conservation project may cash in on new climate action payments. Rossland Telegraph (December 2012). http://rosslandtelegraph.com/news/carbon-neutral-kootenays—darkwoods-conservation-project-may-cash-new-climate-action-payments-22#.UQKfbI5H1UR, return to text

5Approval scheduled for February, 2013. return to text

6Ibid, 2012, return to text

7McDonald&Littlejohn (2010). The Carbon Neutral Kootenays Project: Local Governments and First Nations Reducing Emissions. Retrieved June 7th, 2012 at http://www.cbt.org/pdfs/CNK_Offsets_Strategy_Final_2010-07-19.pdf, return to text

8This is likely the estimated financing for the 3 Phases. The real costs are yet to be determined. return to text

9Littlejohn 2012. Carbon Neutral Kootenays. RDCK Project Update, presentation February 16, 2012. return to text

10The history of the Columbia Basin Trust may have contributed to this type of regional identity in the Province. The CBT is unique in the province, and has been successful in providing Kootenay communities with financial benefits to improve the well-being of their ecosystems and communities in lieu of the considerable hydroelectric activity and provincial profit that comes from the area. (See Background Detailed Case Description). return to text

11McDonald and Littlejohn 2012. return to text

12Ibid, 2012. return to text