Rob Newell

Research Associate, Canadian Research Chair in Sustainable Community Development Program, Royal Roads University

Dr. Leslie King

Professor, Director, Centre for Environmental Education, Royal Roads University

Published January 7th, 2013

Case Summary

First Nations leading the way back to sustainability

T’Sou-ke is a First Nation located on the southwest end of Vancouver Island. T’Sou-ke Nation consists of approximately 250 members, 150 of which live on the reserve, in 96 residences (personal communication, November 30, 2012). The T’Sou-ke community, a sustainable society living on the West Coast for centuries, has since contact been economically involved in forestry and fishing industries (T’Sou-ke Nation, 2009); however, within the past five years, T’Sou-ke has become a leader in community-based renewable energy and food security.

In 2009, T’Sou-ke became BC’s most solar-powered community through their Solar Community Program. Through an involved community effort, T’Sou-ke is now equipped with photovoltaic systems with a capacity of 75 kilowatts of energy (T’Sou-ke, n.d.). This energy flows to the band office, the community hall, the fisheries building, and back to the BC Hydro grid (in exchange for bi-monthly payments from BC Hydro). In addition, 38 homes on the reserve have been equipped with solar hot water installations and all 96 houses have been subject to extensive energy saving programs including Energy Saving Kits (ESKs) and Energy Conservation Assistance Program (ECAP). (personal communication, November 2, 2012), providing direct cost savings to individuals within the community.

T’Sou-ke also has developed a community gardens project, an initiative led by community resident Christine George (personal communication, November 2, 2012). The community established and operates the Ladybug Gardens and greenhouse, located near Edward Milne School (District of Sooke, 2012). Produce from the community gardens is used for weekly events such as Community Lunches and Culture Night as well as a box program for the elderly and celebratory events such as hosting Tribal Journeys that incorporate their 10 mile diet feasts. The gardens hold symbolic significance in terms of the community’s commitment to sustainability (personal communication, November 2, 2012). This commitment has been extended to a new program that includes a 3 acre low energy use commercial greenhouse, partially funded by a $1M grant from the ICE Fund (Innovative Clean Energy Fund). This greenhouse will provide food not just for the T’Sou-ke Community but approximately 30 stores on southern Vancouver Island. The Solar Community Program and the Ladybug Gardens have allowed T’Sou-ke to re-localize their resources in a manner that addresses climate change mitigation and contributes to community resilience and adaptation, as well as providing employment opportunities for youth, stimulating community self-reliance and pride and achieving a measure of community economic self-reliance and stability.

Sustainable Development Characteristics

For the past two centuries T’Sou-ke First Nation has had to make continuous adaptations to a drastically changing world around them mostly brought about by colonization. The fast changing world which has brought about depletion in many natural resources including forestry, fishing and game has had a dramatic effect on T’Sou-ke First Nation’s ability to sustain themselves in traditional or any other sustainable way. Whilst struggling with these huge challenges to livelihood and culture T’Sou-ke First Nation is also affected by one of the biggest challenge facing not just this continent but the whole world – Climate Change.

T’Sou-ke First Nation community’s traditional connection to the natural environment and species related to the land, sea, rivers etc. make them feel that they are ‘the canaries in the coal mine’ as they feel the effects of the changes, short and long term, in increasingly extreme weather patterns. T’Sou-ke Nation located just below the 49th parallel is already struggling with a range of climate change issues including depletion of its traditional fishing industry and the effects of land erosion due to more frequent storms and higher waves. T’Sou-ke believes that all the indications are that this local, national and global phenomenon is only going to get worse. Continuing to building a strong resilient community (T’Sou-ke definition of resiliency = that which bends but does not break) is a pre requisite to a successful sustainability journey.

Re-localization of energy and resources is essential in developing resilient, sustainable communities (Dale, Herbert, Newell, & Foon, 2012), and T’Sou-ke has engaged in this process through use of renewable energy systems and local food production. Through the Solar Community Program, T’Sou-ke has developed the infrastructure to power administrative buildings at a net zero energy expenditure (personal communication, November 2, 2012), and heat water in local residences using a clean, renewable energy source. The community gardens initiative, operating year round, has created a food source that can be harvested without the transaction costs and external reliance involved in importing foods. Because of these re-localization efforts, T’Sou-ke exemplifies sustainable community development in a manner that has fostered an empowered, resilient community with a diversified local economy. The Nation also acts as a mentor and advisor to communities throughout North America and has engaged with a variety of external associations, public and private partnerships and opportunities as well as funding sources e.g. BC Ministry of Energy, Mines and Natural Gas, Federal Ministry Department Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC), BC Hydro and Day for Energy, (Solar PV Manufacturers).

T’Sou-ke has also contributed to sustainability in the ‘broader community’ by engaging in knowledge mobilization. The community has shared their experiences and knowledge on developing solar energy systems and local foods sources with other people and communities using several methods. T’Sou-ke runs eco-tours for local and international groups, featuring the operations of the solar community project, environmental workshops and community gardens (personal communication, November 2, 2012). Representatives of the community frequently attend conferences and workshops to share their knowledge and experiences on how they approached the Sustainability Community Program. In addition, T’Sou-ke has partnered with the Fraser Basin Council, Ministry of Energy, SolarBC, and Xeni Gwet’in First Nation in a collaborative mentorship initiative, referred to a Solar Community Mentorship Initiative, that is design to facilitate sharing solar technology knowledge and expertise with remote and First Nations communities in BC (Fraser Basin Council, n.d.).

T’Sou-ke is a small community of approximately 96 residences, and thus the entire community was able to engage in the sustainability planning processes and energy conservation initiatives (personal communication, November 2, 2012). Community engagement is essential when developing and implementing Integrated Sustainable Community Plans (ISCP) (Ling, Hanna, & Dale, 2009), and, in the case of T’Sou-ke, all members of the community were reached and given the opportunity to provide input on the planning and long-term visioning (personal communication, November 2, 2012). Engaging every member of the community allowed for complete outreach on the importance of energy conservation and conservation strategies, and encouraged empowerment, participation and a sense of ownership in community members.

The philosophy of community has also contributed to T’Sou-ke’s success in developing as a sustainable community. T’Sou-ke ascribes to a philosophy detailed in the Great Laws of the Iroquois Confederacy,

In our every deliberations we must consider the impact of our decisions on the next seven generations.

This concept of being cognizant of the consequences current actions have on those in the future seven generations promotes long-term vision and thus encourages sustainable development (personal communication, November 2, 2012). The community identified four major areas to focus on to achieve a Centre for Sustainability; Energy Autonomy, Food Self Sufficiency; return to Traditional Values and Culture and to become Self-Sufficient Economically. In addition, seven generations of people projects to about 150 years in the future, and considering that current market predictions indicate peak oil could occur in the next few decades (de Almeida & Silva, 2009), a shift from fossil fuel dependency to renewable energy is consistent with T’Sou-ke’s philosophy.

Community Contact Information

Andrew Moore

Solar Community Program Manager

T’Sou-ke Nation

250-642-3957

Andrew@tsoukenation.com

The Solar Energy Program has been very successful in reducing energy consumption and expenditures. T’Sou-ke has estimated a 30% reduction in electricity consumption for individual homes in the community within the first year of the program (T’Sou-ke Nation, n.d.), and all the administrative buildings are net zero in energy consumption. In addition to simply using solar technology, the T’Sou-ke Smart Energy Group (T’SEG) successfully delivers a youth oriented public outreach program on energy conservation not only to the entire community but to a wide range of First Nations, Schools, Universities and other learning institutions. This is achieved through demonstrating the ‘importance of low impact sustainable energy, through the use of culture, traditional values, and historical means of communication” (T’SEG, 2009). As an additional benefit, the T’Sou-ke Solar Community Program essentially created a new skilled local work base by training and employing eleven community members in solar energy system installation.

T’Sou-ke has excelled in knowledge mobilization, and the successes and strategies of the Solar Community Program have been shared with communities across the province and people/organizations throughout the world. External network ties, or bridging ties, are essential for sharing and spreading innovations (Newman & Dale, 2009), and T’Sou-ke has ensured the learning from creating and operating the Solar Energy Program has not been kept in isolation. The Solar Community Mentorship Initiative, in which T’Sou-ke is a partner, is designed to facilitate sharing of knowledge and expertise on developing community solar energy programs to other remote and First Nations communities in BC. In addition, T’Sou-ke connects with local and international people and groups through conferences, their eco-tourism program and their partnership with Solar Colwood and others. Early in 2012 seven T’Sou-ke youth took part in an International food security program which involved producing seven digital stories based on their own and collective experiences at T’Sou-ke – particularly highlighting the T’Sou-ke Zero Mile diet.

What Didn’t work?

The Ladybug Gardens have a high symbolic significance in terms of encouraging community members and visitors to think locally; however, it currently does not produce enough to sustain the community’s nutritional requirements (personal communication, November 2, 2012). Instead, produce created through the gardens is consumed in community events and used in canning workshops led by Christine George (revenue collected through workshops is used for future community events). The community has plans to expand the gardens to four times its current size and generate more local food capacity through an additional greenhouse project, and they hope this expansion and development would satisfy local food needs at T’Sou-ke.

Although the leadership (Chief and Council) of T’Sou-ke Nation has enabled and encouraged the development of the local energy and food projects, T’Sou-ke faces the potential challenge of future leaders not being in support of these sustainability initiatives. In other cases and communities, the changing of municipal government has disrupted the process of sustainable planning and implementation due to shifts in leadership mandates (Newell & King, 2012), and T’Sou-ke leadership changes on a two-year cycle, which makes the community vulnerable to shifting focuses in governance. However, this is currently only a potential challenge, as the solar energy and community gardens initiatives have been enthusiastically supported by community leaders and members to the present. T’Sou-ke stresses that starting a sustainable development program with comprehensive community buy-in is an important risk management strategy.

Financial Costs and Funding Sources

The initial funding for the community solar energy system was provided through the Innovative Clean Energy (ICE) Fund administered by the Ministry of Energy and Mines. This initial sum amounted to $400,000, and it allowed T’Sou-ke to leverage another $900,000 to complete the project (personal communication, November 2, 2012). Specific numbers for the energy conservation program are in the region of $300,000 including contributors such as BC Hydro, Live Smart BC, NRCan, Solar BC – in all the energy project engaged over twenty different private and public sector funders.

Funding sources for the community gardens are varied and include the Vancouver Island Health Authority (VIHA), Sooke Regional District, Van City, and the Victoria Foundation. T’Sou-ke is expecting to secure an additional $200,000 in funds from the Ministry of Agriculture in exchange for using their community food programs as demonstration model for similar programs proposed for remote northern BC communities. T’Sou-ke intends to use these funds to expand their community gardens to approximately four times current size.

Detailed Background Case Description

Both the philosophy and history of T’Sou-ke as a First Nations community have been strong drivers of the community’s sustainable development pathway. The community philosophy and principles involve honouring and expressing gratitude to the Earth (personal communication, November 2, 2012), and T’Sou-ke adheres to the concept of operating a community in a manner that is mindful of the next seven generations (see Critical Success Factors). In terms of the historical context, Linda Bristol, T’Sou-ke Elder, noted that First Nations communities have had to adapt to severe challenges throughout their history, including foreign diseases introduced by the colonial regime, the residential school system, and loss of traditional lands (personal communication, November 2, 2012). The combination of long-term vision and high adaptability has contributed to T’Sou-ke Nation’s drive and ability to address climate change – both mitigation and adaptation.

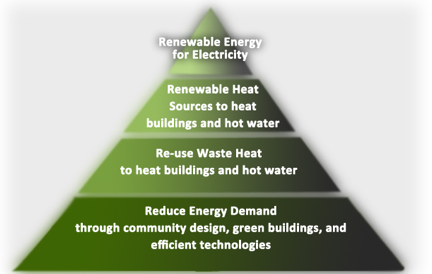

When T’Sou-ke deciding to engage in a focused effort to mitigate through GHG reduction and adapt to climate change and increase community resilience, the community approached this work from what Andrew Moore, Solar Community Program Manager, describes in retrospect as the ‘the top of the triangle’ (personal communication, November 2, 2012). What Moore is referring to is a pyramid model for a sustainable energy pathway (see diagram below) that identifies the following steps, from bottom to top: reduce energy demand, reduce energy waste, use renewable energy for heat, and use renewable energy for electricity (diagram below adapted from presentation slides prepared by T’Sou-ke Nation, adapted from Gary Hammer’s Energy Planning Hierarchy, BC Hydro).

T’Sou-ke initially sought out funding for the installation of solar energy system for electricity and heat in administrative buildings (and then for hot water heat in residences), and this effort was complemented with reducing energy demand through their energy conservation outreach and education program. Although this process could be viewed technically as ‘implemented backwards’ in terms of the aforementioned pyramid model, psychologically it was carried out with forward thinking. Taking steps toward an ambitious and innovative renewable energy system promoted a strong commitment toward sustainability and ultimately aided in the processes of achieving community buy-in with energy conservation (personal communication, November 2, 2012). Although the community is now seen to have started at the wrong end of the triangle, taking the dramatic step of generating renewable energy and building the solar arrays, while the more expensive step on the triangle grasped the attention of the community and promoted engagement and the motivation necessary to move down to the bottom of the triangle (Reducing energy demand). Without the top piece of the triangle it is questionable whether the other steps on the triangle could be achieved.

The solar energy system consists of approximately 550 solar panels and is the largest community solar energy system in BC (personal communication, November 2, 2012). Solar energy powers both heat and electricity in the administrative buildings, and surplus energy in the summer is sold back to BC Hydro, effectively creating a net zero energy expenditure (personal communication, November 2, 2012). Currently, 38 houses in T’Sou-ke have been fitted with a solar water heating system, and the community aims to equip all residences with solar water heating. The complementary energy conservation program is operated by the T’Sou-ke Smart Energy Group (T’SEG), and it uses public outreach methods (such as creating and distributing educational materials, community events, and social media) to raise awareness about the environmental and economic benefits of saving energy (T’SEG, 2009).

In addition to engaging in local energy production, T’Sou-ke also has taken steps to engage in local food production through their community gardens and greenhouse. T’Sou-ke established Ladybug Gardens, their community gardens, in reaction to the awareness that Vancouver Island imports approximately 95% of its food products and a need for local food security is critical (T’Sou-ke Nation, n.d.). The gardens currently do not produce enough food to sufficiently support the community; however, T’Sou-ke plans to expand the gardens to four times its current size when funding becomes available (personal communication, November 2, 2012). Currently a business Plan is being prepared by MNP accounting consultants to help raise another $1M for the three acre commercial greenhouse. Construction is expected to start on site June 2013. Production of tomatoes and or peppers is planned to start spring 2014.

T’Sou-ke’s sustainable development pathway was highly inclusive and provided all the community members with opportunities for input and involvement. The community held a series of focus groups and community meetings when developing their long-term vision for sustainable development planning (personal communication, November 2, 2012), and community members that were absent from these meetings were later approached for their opinions (personal communication, November 2, 2012). The meetings were designed to be ‘fun’ and engaging through the use of activities, and meeting participants were strongly encouraged to share their opinions and ideas to maximize community input (T’Sou-ke Nation, n.d.). This engagement process did not end but continues to the present and will continue in the future to ensure ongoing community participation and governance of the project and sustainability process. The comprehensiveness and extensiveness of the community engagement process fostered a unity of vision and greatly contributed community participation in sustainability initiatives (personal communication, November 2, 2012).

T’Sou-ke’s sustainability innovations have been shared with many other people, communities and organizations through partnerships, eco-tourism and conferences (see Sustainable Development Characteristics and What Worked?). The community is regarded as a model example of how to implement strategies for increasing sustainability and community resilience, and, through Solar Community Mentorship Initiative, T’Sou-ke aids other communities in developing community sustainability programs. T’Sou-ke has recently partnered with the nearby municipality of Colwood, Royal Roads University and others to provide advice, expertise and solar installers to the Solar Colwood initiative (Solar Colwood, n.d.). This initiative aims to equip approximately 1,000 homes with energy saving devices, using an operating budget of $12 million (personal communication, November 2, 2012).

Resources and References

Dale, A., Herbert, Y., Newell, R., & Foon, R. (2012). Action agenda: Rethinking growth and prosperity. Canadian Research Chairs in Sustainable Community Development, Royal Roads University. In partnership with Sustainability Solutions Group. Retrieved November 30, 2012, from http://crcresearch.org/sites/mc-3/files/u641/action_agenda_rethinking_g…

De Almeida, P., & Silva, P. (2009). The peak of oil production—Timings and market recognition. Energy Policy, 37(4), 1267-1276.

District of Sooke. (2012). Community roots: An agricultural plan for Sooke. Draft. Retrieved November 30, 2012, from http://www.sooke.ca/EN/main/government/devservices/planning/documents/A…

Fraser Basin Council. (n.d.) Remote Community Implementation (RCI) Program: Solar Community Mentorship Initiative. Retrieved November 30, 2012, from http://www.fraserbasin.bc.ca/programs/caee_rci_solar_mentorship.html

Ling, C., Hanna, K., & Dale, A. (2009). A template for integrated community sustainability planning. Journal of Environmental Management, 44(2), 228-241.

Newell, R., & King, L. (2012). Prince George. Meeting the Climate Change Challenge (MC3) case study. Partnership project, Royal Roads University, University of British Columbia, and Simon Fraser University. Retrieved November 29, 2012, from http://www.mc-3.ca/prince-george

Newman, L., & Dale, A. (2009). Homophily and agency: Creating effective sustainable development networks. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 9(1), 79-90.

Solar Colwood. (n.d.). Solar Colwood partnerships. Retrieved November 30, 2012, from http://www.solarcolwood.ca/partnerships.php

T’Sou-ke Smart Energy Group. (2009). T’Sou-ke Smart Energy Group. Home page. Retrieved November 30, 2012, from http://www.tsoukenation.com/2009/07/tsou-ke-smart-energy-group

T’Sou-ke Nation. (2009). T’Sou-ke Solar Gathering. Brochure.

T’Sou-ke Nation. (n.d.). Comprehensive Community Planning Creating Sustainable communities. Presentation slides.

T’Sou-ke Nation. (n.d.). Implementing Adaptive Capacity: T’Sou-ke Nation. Interactive online presentation. Retrieved November 30, 2012, from http://www.cier.ca/implementing-adaptive-capacity.html

T’Sou-ke Nation. (n.d.). T’Sou-ke Solar Community. Presentation slides.

Acknowledgements: The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance and collaboration of the Chief and members of the T’Sou-ke Nation and Andrew Moore and elder Linda Bristol for their unflagging devotion to sharing knowledge about the T’Souke experience and innovative responses to the challenges of climate change and sustainability.